Introduction

One of the most discussed issues in Major League Baseball is the consistency of the strike zone. The Rule Book strike zone states “The STRIKE ZONE is that area over home plate the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level is a line at the hollow beneath the kneecap. The Strike Zone shall be determined from the batter’s stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball.” After watching games throughout the regular season and playoffs, it is easy to realize this is not the strike zone that is called. Each umpire has tendencies and dictates his own strike zone and how he will call a game. With the rise of PITCHf/x and Trackman in the last few years, umpires have been increasingly monitored and judged for their accuracy and impartiality. For this reason, umpires are criticized for incorrect calls more than ever before and I believe are now trending towards enforcing the Rule Book strike zone more than in years past.

The purpose of this research will be to do two things. First, I will focus on identifying overarching themes where I look at finding how umpires are adjusting to modern technology but also how the Rule Book strike zone is not the strike zone we know. After this, I will dive into a few umpire-specific tendencies. The latter would be helpful to teams in preparing their advance reports by knowing how certain umpires call “their” strike zone dictated by situations in a game.

Analysis

Using PITCHf/x downloaded through Baseball Savant, I have looked at major league umpires since 2012 in regards to their accuracy in correctly labelling pitches, primarily strikes, and their tendencies dictated by specific situations. While the height of the strike zone is often influenced by the height of the batter, there are other factors to take into account such as the how the batter readies himself to swing at a pitch. Unfortunately, the information publicly available to conduct this research does not include the batter handedness, pitcher name, or measurements of individual strike zone limits. For this reason, a stagnant strike zone serves our needs best. The height of the strike zone shall be known as 1.5 feet from the ground to 3.6 feet from the ground. This is the given strike zone of a batter while using the pitchRx package through RStudio when individual batter height is not included. All PITCHf/x data is from the Catcher/Umpire perspective, having negative horizontal location to the left and positive to the right. The width of home plate is 17 inches, 8.5 inches to both sides where the middle of the plate represents 0 inches. After calculating the average diameter of a baseball at 2.91 inches, we add this to the width of the plate. Therefore our strike zone width will be 17 + 5.82, or 22.82 inches. The limits we will then set are going to be -.951 to .951 feet (or 11.41/12 inches). Throughout the paper I will be referring to pitches that fall within the boundaries of our zone as “Actual Strikes” and pitches correctly identified as strikes within this zone as “Correctly Called Strikes.”

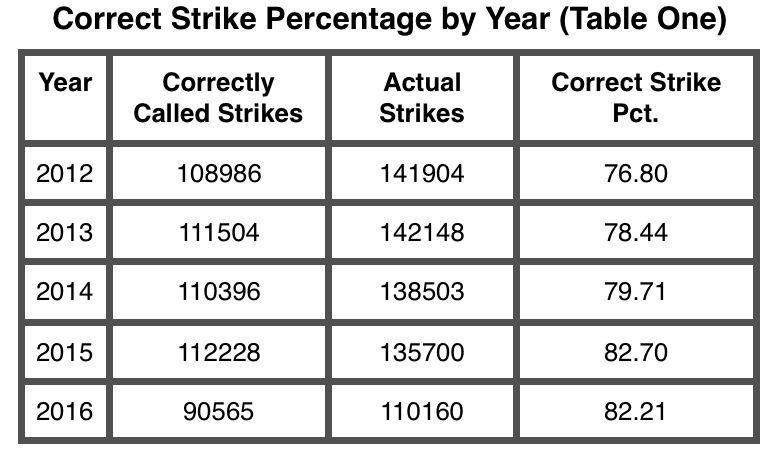

Called Strike Accuracy By Year

As Table 1 shows, correctly identifying strikes that fall in the parameters of the Rule Book strike zone has risen substantially. While 2015 has a higher percentage of correctly called strikes, 2016 PITCHf/x data from Baseball Savant was incomplete with 28 days worth of games unavailable at the time of this research. A rise of 5.90 percent correctly called strikes from 2012 to 2015 shows the Rule Book strike zone is being more strictly enforced.

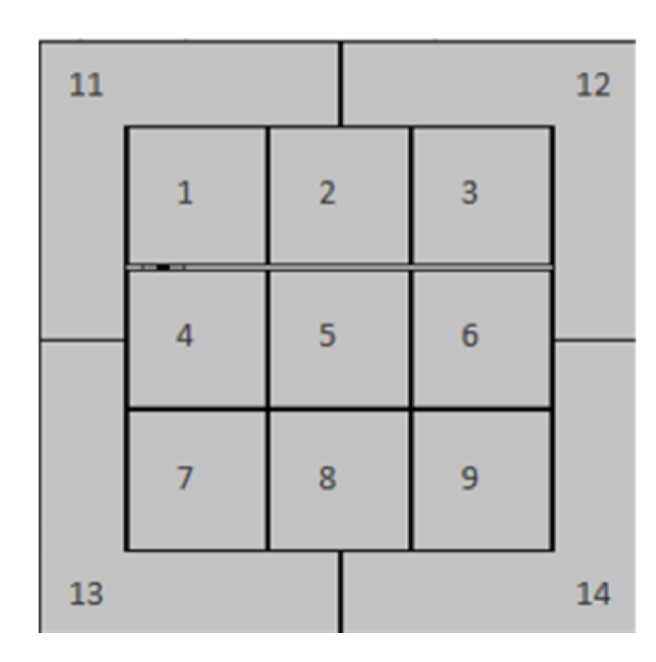

While this provides some information, we can also look into where strikes are correctly being called using binned zones. Understanding that the evolution of umpires over the last 5 years is taking place and trending towards correctly identifying strikes more today than in years past, we can analyze where in the strike zone, strikes have been correctly labeled.

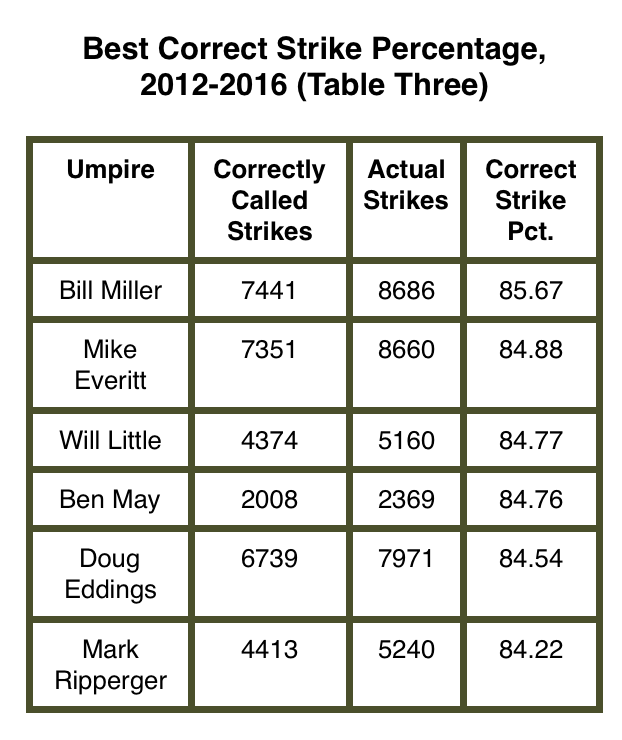

Called Strike Accuracy by Pitch Location

In Table 2, we can see a tendency amongst umpires. Strikes are called strikes more routinely over the middle of the plate and to the left (from umpire perspective). As I have mentioned before, the publicly available PITCHf/x data I used did not include batter handedness and I am unable to determine who is receiving the benefit or disadvantage of these calls. Presumably from previous research on the subject, lefties are having the away strike called more than their right handed counterparts, explaining the separation between correctly identifying strikes in zones 11 and 13 versus 12 and 14.

While one may argue that there should not be strikes in these bordering zones, we consider any pitch that crosses any portion of the plate a strike. Due to our zone including the diameter of the baseball on both sides of the plate, the outer portion of the plate includes pitches where the majority of the ball is located in one of these zones.

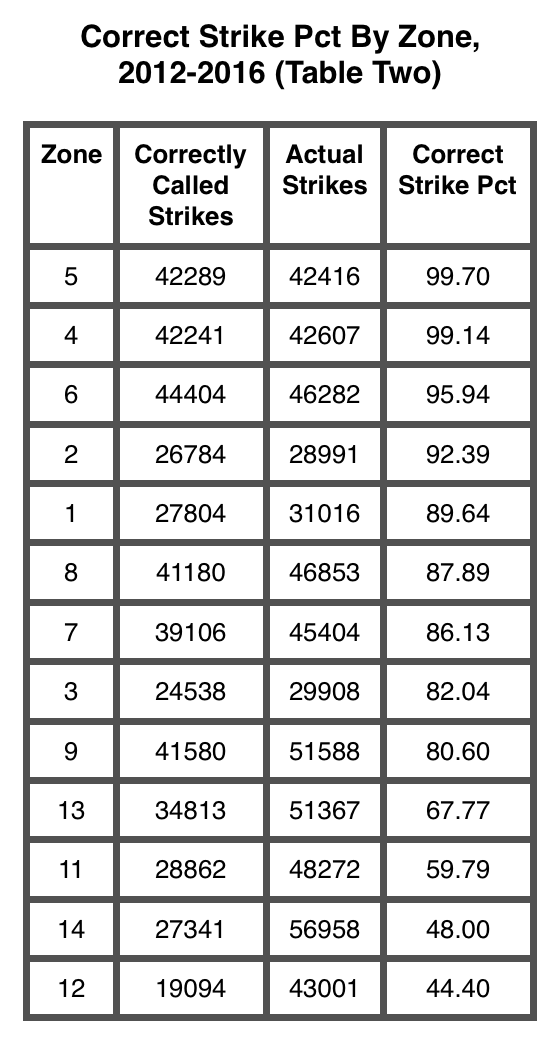

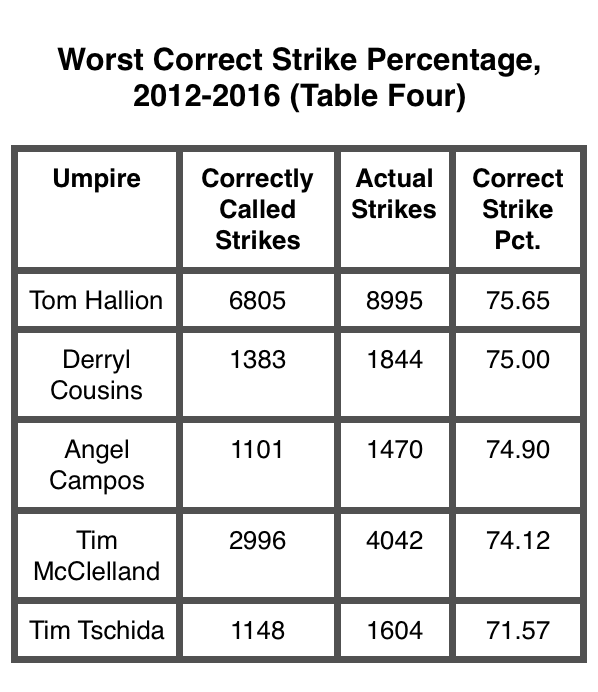

Called Strike Accuracy by Individual Umpire

When gauging an umpires ability to correctly identify a Rule Book strike, an 85.67% success rate sets the mark with Bill Miller, while Tim Tschida ranks at the bottom of this list, only calling 71.57% correctly. We can infer from Tables Three and Four along with Table One, that while umpires are calling strikes within the strike zone more often, they are still missing over 17% of these pitches. It is important to note that this information does not take into account incorrectly identifying pitches outside the Rule Book strike zone as strikes, which when considering an umpire’s overall accuracy, should absolutely be taken into account.

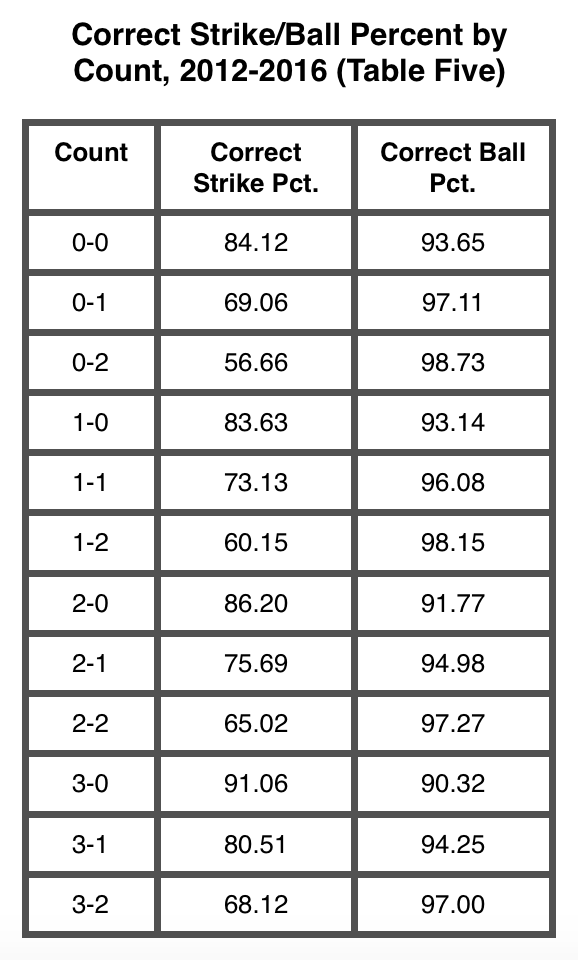

Called Strike and Ball Accuracy by Count

One of the most influential factors in whether a taken pitch is called a strike or a ball is the count of the at bat. We have all seen pitches in a 3-0 count substantially off of the plate called a strike, just as we have seen 0-2 pitches over the plate ruled balls. Table Five shows the correct percentage of strikes and balls by pitch count. While this shows that umpires are overwhelmingly more accurate at identifying strikes as strikes in a 3-0 count (91.06%) as compared to an 0-2 count (56.66%), we must acknowledge this only paints part of the picture. Umpires are conversely most likely to correctly labels balls in 0-2 (98.73%) counts and misidentify balls in 3-0 (90.32%) counts. I included their accuracy of correctly identifying both strikes and balls here as opposed to throughout the entire paper because we can clearly tell through this information that umpires are giving hitters the benefit of the doubt over pitchers. Umpires are far more likely overall to correctly identify a ball than a strike, as evidenced by the fact that there are no counts during which umpires correctly call less than 90% of balls.

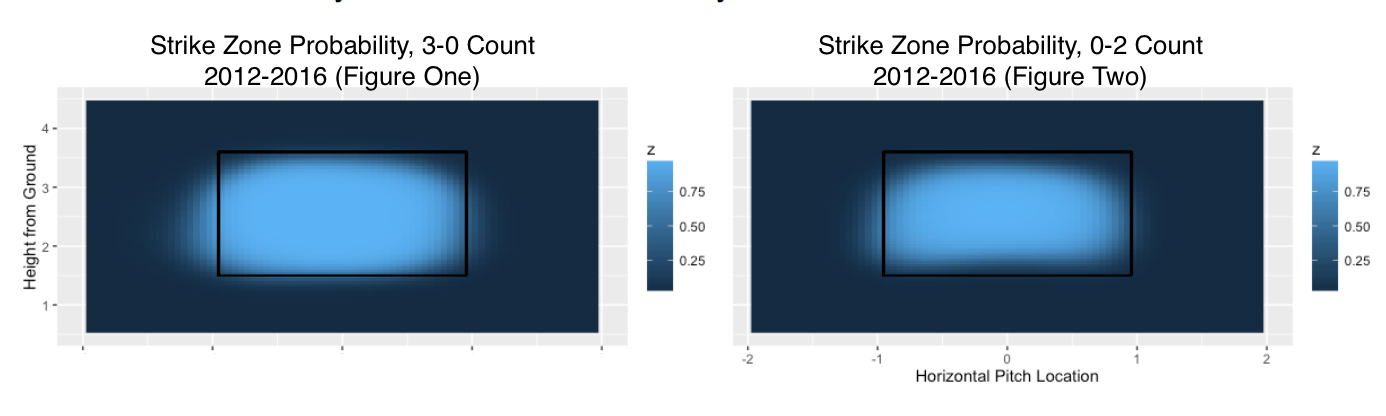

The data in Table Five is corroborated by the visualizations in Figure One and Figure Two. These visualizations of the strike zone include pitches off of the plate and we can see that in a 3-0 count, a more substantial portion of the Rule Book strike zone is called strikes while also incorrectly identifying balls as strikes. While in a 0-2 count, a smaller shaded area of the Rule Book strike zone works with our findings that less strikes are identified correctly but more balls are correctly called.

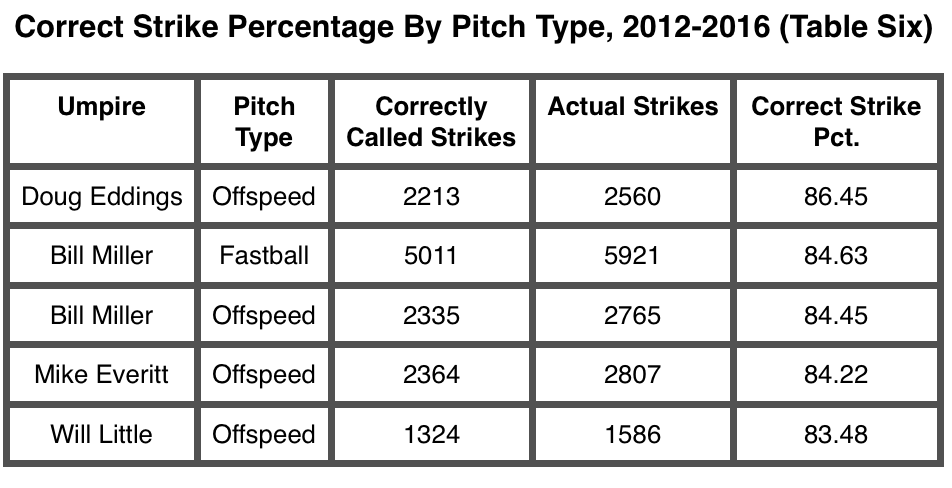

Called Strike Accuracy by Pitch Type

The next area I looked at was whether pitch type significantly altered the accuracy of umpires. In order to do this, I grouped all variations of fastballs into “Fastball” and all other pitches into “Offspeed”, while omitting pitch outs and intentional balls. I was able to see how umpires fared in correctly identifying strikes by pitch type in Table Six.

Not surprisingly, we see Bill Miller near the top of the list with both Offspeed and Fastball accuracy. For umpires as a whole, the difference in accuracy between the two is not large (79.05% Offspeed accuracy vs. 78.91% Fastball strike accuracy). On the other hand, what may come as a surprise is the fact that eight of the top ten highest accuracies were for Offspeed pitches.

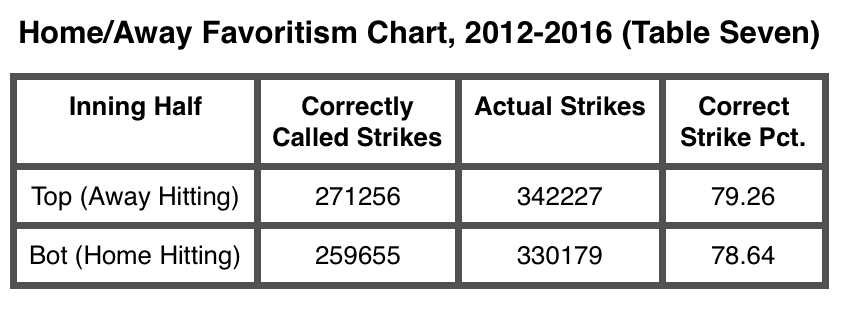

Called Strike Accuracy for Home and Away

One of the most mentioned tendencies of referees or umpires in any sport is home team favoritism. Whether a foul or no foul call in basketball, in or out of bounds call in football, or a strike or ball ruling in baseball, many think that the home team receives more of an advantage than their visiting counterparts. Looking at top and bottom half of innings, away and home team respectively, we can identify trends and favoritism in major league umpire strike zones.

While a difference of .62% accuracy may seem like a lot, especially in a sample size of over 650,000 total pitches, we can look at this on a game by game level to see the actual discrepancies. For simplicity’s sake, we can assume 162 games a season, making for roughly 11780 games played in our data set (this subtracts all games from the unavailable 2016 data). This leaves us with 23.03 Correctly Called Strikes out of 29.05 Actual Strikes for away teams per game, meaning that 6.02 strikes were not called. As for home teams, we have 22.04 Correctly Called Strikes a game with 28.02 as the Actual Strikes, averaging 5.98 missed strikes a game. By this measurement we can see that more hitter leniency was given to the away team than the home team.

During this time frame, while a higher percentage of strikes were judged correctly, hitters were given more leniency as the away team than the home team on a game-by-game basis.

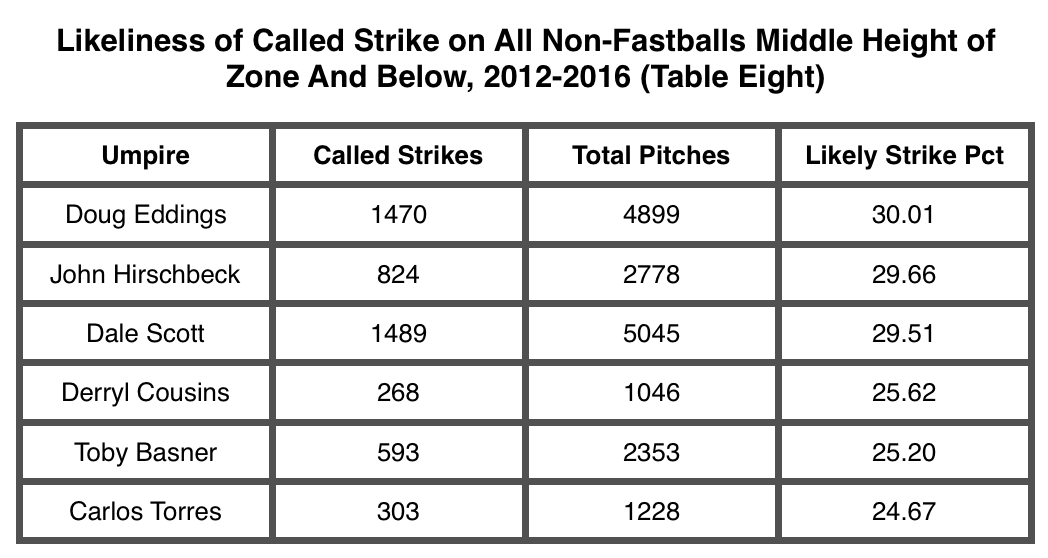

Called Strike Likeliness in Specific Game Situation

Included in Table Eight are the three most and least likely umpires to call any non-fastball a strike below the vertical midpoint of our zone. I split the strike zone at 2.55 vertical feet and looked at any pitch (not necessarily within the zone) below that height. Here, we are not judging an umpires accuracy of correctly identifying pitches but rather looking at where a certain umpire may call specific pitches. We can see that Doug Eddings is 5.34% more likely to call a strike on a non-fastball as compared to Carlos Torres.

While this does not paint the entire picture, we are able to see how their tendencies can play an important role in the game. Information like this may be valuable to a team in deciding how to pitch a specific batter, which reliever to bring into a game, or factor into being more patient or aggressive while at the plate.

Conclusion

External pressures and increased standards are undoubtable effects on umpire strike zones. As evidenced throughout this paper, strike zones are called smaller than the Rule Book strike zone specifies. And while umpires are trending towards correctly identifying strikes, situations such as count and pitch type can affect their judgment.

While the system in place is not 100%, we must understand that these umpires are judging the fastest and most visually deceptive pitches in the world and are the best at what they do. Major League Baseball must use modern technology to their advantage and provide the best training for umpires to achieve the goal of calling the Rule Book strike zone. Another option, while more drastic and difficult to implement, may include adapting the definition of the Rule Book strike zone, something that has not been changed since 1996.